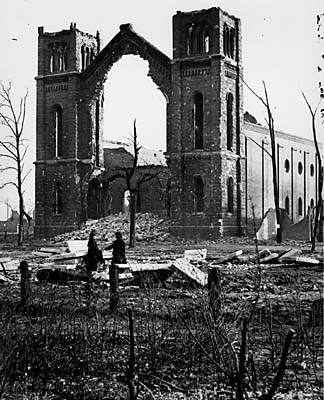

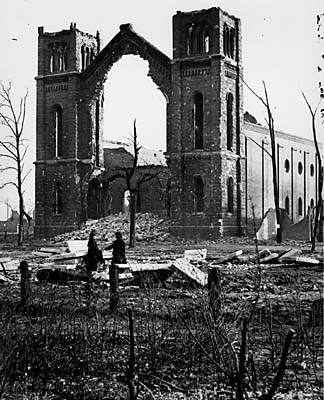

The Ruined City

{Main}

Devastated Chicago remained so hot that it took a day or two before it was possible even to begin a survey of the physical damage. According to the papers, in some instances when anxious businessmen opened their safes among the rubble of what was once their offices, precious contents that had survived the inferno suddenly burst into flame on exposure to the air. Shortly after the fire, Stephen L. Robinson, a North Division resident whose home was not burned, set out with a printed map of the city to mark what was still standing. Among the few scattered survivors he noted were the mansion of Mahlon Ogden (brother of William) on Lafayette (now Walton) Street north of Washington Square Park, and the other much more modest home north of Armitage of police officer Richard Bellinger, bof which were saved by good luck. And had he reached the South Division, he would have seen the Lind Block standing a forlorn watch over the downtown. Had he then crossed to the West Division, he would have found the O'Leary cottage safe and sound in front of the ashes of the barn.The so-called "Burnt District," a map of which appeared in virtually every account of the fire, encompassed an area four miles long and an average of three-quarters of a mile wide--more than two thousand acres--including over twenty-eight miles of streets, 120 miles of sidewalks, and over 2,000 lampposts, along with countless trees, shrubs, and flowering plants in "the Garden City of the West." Gone were eighteen thousand buildings and some two hundred million dollars in property. Around half of this was insured, but the failure of numerous companies cut the actual payments in half again. One hundred thousand Chicagoans lost their homes, an uncounted number their places of work.